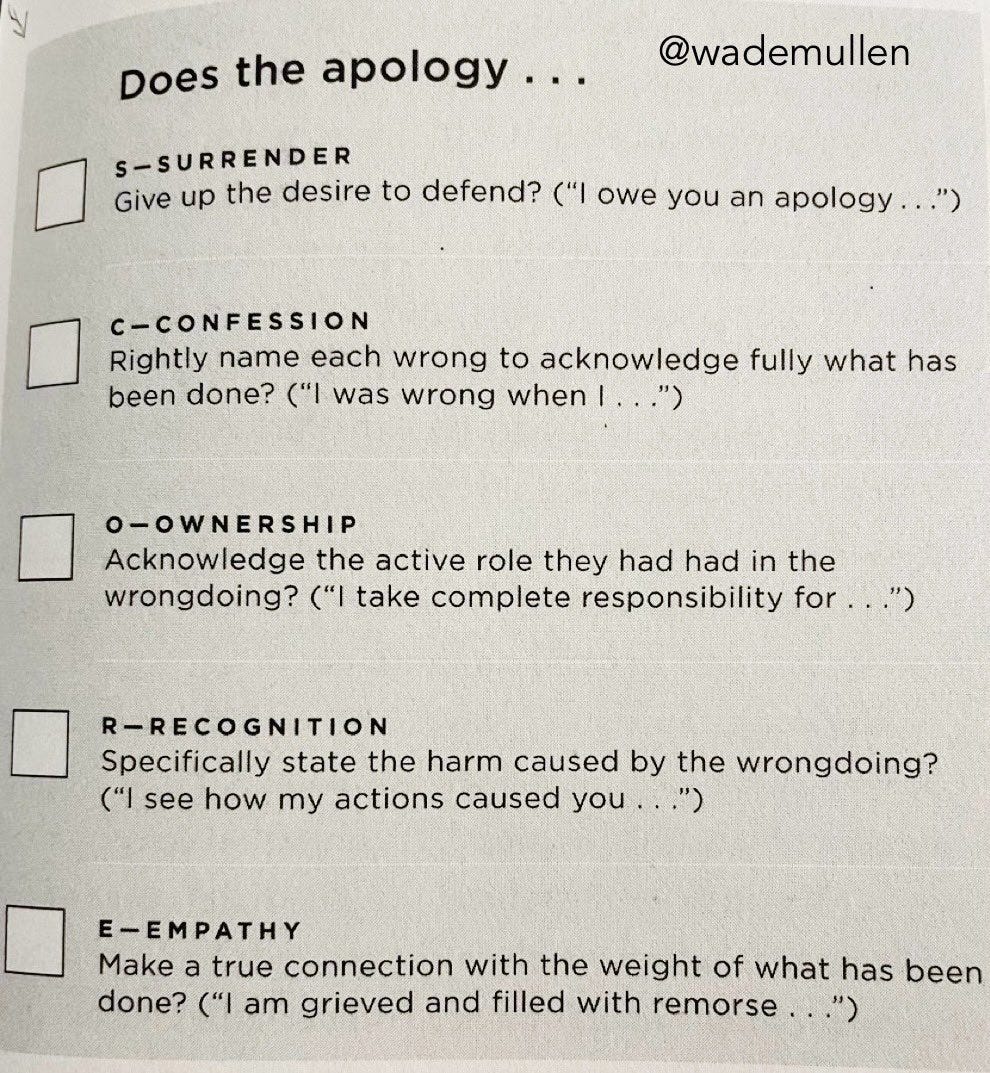

Chuck DeGroat, whose work I highly recommend, posted a graphic on social media from my book Something’s Not Right that depicts an acronym I developed to help readers identify five elements of a meaningful apology.

Anytime there is a discussion about giving authentic apologies, I hear from those who describe the confusing experience of being on the receiving end of pseudo-apologies, particularly of the variety containing the two-letter word “if.”

In this post, I present two types of pseudo-apologies that include “if” statements. These pseudo-apologies are also mentioned in Aaron Lazare’s book On Apology.

The apology that does not admit to any wrongdoing: “I’m sorry if mistakes were made.”

The apology that does not admit to any injury: “I’m sorry if you were hurt.”

To the listener, the word “if” introduces them to the possibility that the wrongdoing or injury in question might not have actually occurred. “If mistakes were made” suggests that perhaps mistakes were not made. “If you were hurt” suggests that perhaps you were not really hurt or others in a similar situation would not have been hurt.

In some of the encounters I’ve had with these types of apologies, it turned out that the apologizer didn’t actually believe any wrongs were committed, but were insincerely offering a line they hoped would be accepted.

An Example

In a 2002 communication regarding the Roman Catholic Church’s sexual abuse crisis, Cardinal Edward M. Egan, the leader of the New York Archdiocese, illustrates this conditional apology. He commented:

If in hindsight we also discover that mistakes may have been made as regards prompt removal of priests and assistance to victims, I am deeply sorry.

Years later, Egan was interviewed by Connecticut Magazine and asked about his 2002 apology. Egan claimed he should have never said it because he didn’t believe they did anything wrong.

CT Magazine: In 2002, you wrote a letter to parishioners in which you said, “If in hindsight we discover that mistakes may have been made as regards prompt removal of priests and assistance to victims, I am deeply sorry.”

EGAN: First of all, I should never have said that. I did say if we did anything wrong, I’m sorry, but I don’t think we did anything wrong.

Pseudo-apologies can contain a double betrayal. The first betrayal is in the communication itself, which on the surface might seem like a genuine effort to acknowledge the truth and amends, but is actually cloaked in conditions. The second betrayal is in the realization, if it ever comes, that the apologizer doesn’t actually believe they needed to apologize to begin with but was hoping you’d be fooled.

The Goal of “I’m Sorry If . . .” Statements

Why are variations of these two “if” statements so often included in apology statements? I’m sure there are a variety of mixed reasons and motivations, but the two that I’ve repeatedly come across include: (1) Fear of what will happen if an apology is offered without conditions; (2) Anger or resentment toward those who, in the eyes of the wrongdoer, simply won’t move on until they get an apology.

So rather than offer a genuine apology, the wrongdoer presents what I call a “concession” to appease those who are attempting to establish the truth, pursue justice, and promote repair. The wrongdoer can be firmly convinced they’ve done nothing that would merit an apology, but offers one strategically in order to satisfy what they believe others want. Their thinking goes something like this: “If I just say that I’m sorry people will move on and we can put this behind us.” And in doing this, they might actually believe they are taking the high road and being the bigger person by generously offering a fake apology to those they treat with hidden condescension.

In his book On Apology, Lazare writes:

In such situations, the wrongdoer is saying in effect, “Not everyone would be offended by my behavior. If you have a problem with being so thin-skinned, I will apologize to you because of your need (your weakness) and my generosity. I hope this makes you happy.” Notice how the form of this apology transforms the victim into the cause of the offense and the offender into a blameless and generous benefactor.

One of the indicators of this attempt to simply appease others by offering a pseudo-apology is how the wrongdoer responds when their conditional apology isn’t accepted. Responses I’ve seen include something like: “I said I was sorry. What more do they want?” Or the response is to remain silent and not engage further.\

Responding to Pseudo-Apologies

It can be difficult to know how to respond to a pseudo-apology. If it’s safe to do so, you can respond by asking questions like, “Do you believe you did anything wrong? Do you believe anyone was hurt? What exactly are you apologizing for?” Sadly, apologies offered by those in power, such as institutional statements, often don’t provide any opportunity for a response, so people are left with little recourse. And even if there is opportunity for dialogue, rejecting an apology can be met with accusations that you are being ungracious, nit-picky, and bitter.

You aren’t being nit-picky, ungracious, or bitter when you reject a pseudo-apology. Rather, you are valuing truth-telling and giving the other person an invitation to step into the freedom of truth and participate in a process of repair. But it can be very difficult for someone or an institution used to being in control to offer a truth-filled apology, so that invitation to truth-telling might be viewed as a threat to their power.

I often get asked how about the differences between an authentic apology and a concession. While there is much that can be identified in the words themselves, the most significant factors seem to be power and control. Pseudo-apologies retain control of the outcome by using deception. Authentic apologies surrender that control.

Alice Walker, whose best-known work is The Color Purple, was interviewed for a collection of published conversations with notable writers titled More Writers & Company: New Conversations with CBC Radio's Eleanor Wachtel. Eleanor Watchel asked Alice Walker what her father taught her about truth-telling when she was very young:

Wachtel: You say that your father taught you something very important: not to bother telling lies because the listener might be delighted with the truth.

Walker: When I was three or four, I broke a jar, and given that I had siblings I could have said that they had broken it, or I could have said that it had slipped. I remember that he asked me if I had done it, and I looked at him and I thought, gee, this is a person I really love and he would be happy if I hadn’t broken this thing. On the other hand he was looking at me with such expectancy that I found myself coming up to meet his expectancy with a real need to express the truth, because that’s the most wonderful feeling there is. So I said, “Yes, I broke the jar.” His response was not to fuss and not to spank me or anything but rather to beam this incredible love in my direction, and that was his way of teaching me about telling the truth and what is possible. It is possible that if you tell the truth not only will you be delivered yourself from the prison of untruth, but the person who hears the truth will also be opened and can be delighted.

Later in the conversation, she noted the difference between the creative and destructive capacities of our words and actions and how, “if you lie, you’re constantly trying to remember what you lied about and how you lied.” The attempt to control the narrative through deception becomes a kind of psychic prison. It’s much better to speak the truth.

M. Scott Peck made this point in his book The Road Less Traveled:

The more honest one is, the easier it is to continue being honest, just as the more lies one has told, the more necessary it is to lie again. By their openness, people dedicated to the truth live in the open, and through the exercise of their courage to live in the open, they become free from fear.

An apology in its purest form is offered without excuses, justifications, conditions, comparisons, and self-promotion. It surrenders power and control in service of truth and repair. And it brings hope to the possibility of lasting change - the true test of sincerity.

For more on institutional apologies, revisit my first post: What I’ve Observed When Institutions Try to Apologize and How They Can Do Better.

Thank you Wade 🙏 What if a person/institution uses Chatgpt to craft an apology that sounds like it is authentic but was purely written by an AI robot and read out... Without acknowledging specific wrongs or specific people injured 😢 This happened to us

Wade, thank you for laying this out so clearly, for giving words where there were none, for labeling things rightly.