The Toxic Triangle

Understanding how systems enable abuse

Early on in my journey to understand abusive systems and dynamics, I was pointed to a talk by Dr. Diane Langberg titled Narcissism and the Systems it Breeds, which I share in this post. As I further studied the topic as part of my PhD research, and later taught courses on power and leadership, I began to see the importance of thinking in systems as it relates to these topics, to borrow from the title of Donella Meadows’ fascinating book Thinking in Systems. One of the frameworks that is helpful for thinking about abusive environments as a system, and which has spurred many conversations with others who I’ve been on this learning journey with, is The Toxic Triangle.

A Brief Overview of The Toxic Triangle

When people ask, “How did this happen?” they’re often searching for a single point of failure. Was it a destructive leader? A non-existent or weak policy? A failure of bystanders to speak up? The best way to approach answering this question is to think in systems, understanding how a set of parts might work together in an interconnected network.

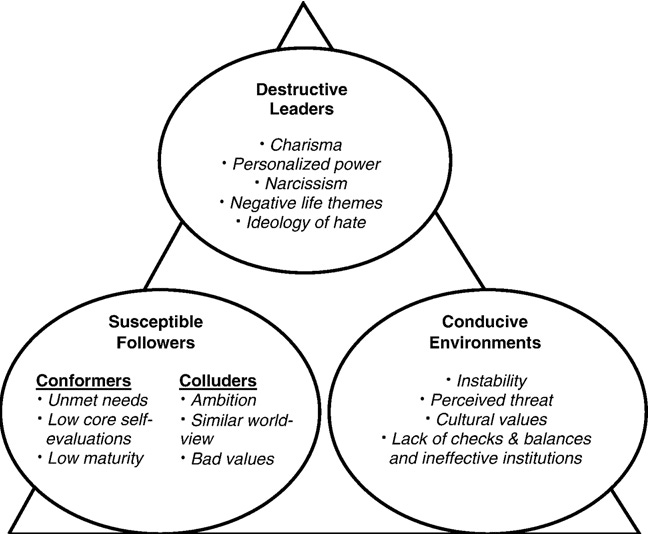

In 2007, researchers Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser introduced a framework called the Toxic Triangle to explain how destructive leadership emerges not as an isolated phenomenon, but through the convergence over time of three critical factors:

Destructive Leaders

Susceptible Followers

Conducive Environments

It helps explain why simply removing a toxic person, while potentially significant, doesn’t always solve the problem. The structure that enabled the harm might still be in place.

Destructive Leaders

These individuals are characterized by traits such as narcissism, charisma, and a personal drive for power and dominance. Their leadership is marked by coercion and manipulation, often cloaked in charm or visionary rhetoric. They may have histories of negative life experiences, which can fuel an ideology of hate or a need for control.

They may frame disagreement as disloyalty, interpret critique as a personal attack, use charisma or ideology to justify control, and surround themselves with people who protect their image.

Some destructive leaders don’t simply rise within broken systems but rather construct them for their own benefit. The system becomes an extension of their ego. Their needs become the organizing principle. Their image becomes sacred. Others orbit around them, not out of trust, but out of fear or obligation.

Dr. Diane Langberg, a clinical psychologist and trauma expert, has explored this dynamic in her lecture, Narcissism and the Systems It Breeds. I highly recommend it if you’re looking to understand how entire systems can be structured to serve the self, not the truth.

Susceptible Followers

Destructive leaders don’t always act alone. They might be enabled by the people around them. Padilla and colleagues identified two primary types of followers:

Conformers comply to belong, avoid punishment, or preserve status

Colluders align with the leader to gain power or protect shared goals and values

But in high-control systems, people respond to pressure in different ways and I think it is important to distinguish between those who collude for their own advancement at the expense of another’s well-being and those who conform for their own protection. Erving Goffman, writing about life in a total institution, a system where everything about a person’s life is controlled by the institution, outlined four common responses:

Conversion — fully adopting the beliefs and values of the system

Compliance — outwardly conforming to stay safe or accepted

Withdrawal — emotionally or relationally disconnecting

Opposition — resisting the system, often at great personal cost

I find these types of responses to be similar to those trying to find their way in a toxic triangle. If you find that you now oppose a system you once were a part of, you may look back on a time when you were once sincerely converted to the beliefs and values before threats emerged that caused you to move from conversion to compliance to withdrawal to opposition.

You may also shift between these responses over time. You might comply in the presence of others, withdraw in private, and resist internally. These are adaptive responses to environments where power is enforced through fear, manipulation, or reward. It’s important to have compassion toward yourself and others trying to discern truth and preserve safety in a destructive system.

Conducive Environments

The final piece of the triangle is the environment. Certain environmental conditions make it easier for destructive leadership to thrive:

Crisis or instability that makes people more receptive to control

Loyalty culture, where questioning is equated with betrayal

High power distance, where leadership is idealized and unchecked

Contradiction between what’s said and what’s done

Lack of accountability

Non-existent, weak, or unenforced policies

These environments can be shaped by the destructive leadership. For example, a board can be hand-picked by a destructive leader to ensure only loyalists are included, thereby weakening accountability. Policies can be crafted to support the top rungs of the hierarchy, rather than protect the rights and interests of all.

Environmental changes can also be an area of organizational self-promotion when a toxic system is exposed but doesn’t want to address its destructive leadership. So they might point to existing or newly created procedures, policies, or public statements as proof of its integrity. This is when it is helpful to think in systems. The presence of policy does not equal the presence of safety. Systems can adopt the language of protection while continuing to function in harmful ways. New policies won’t change a system that lacks the will or character to apply them with integrity.

Thinking in Systems

Harmful communities and organizations rise and fall as a system, which explains why the solution is not always to simply remove destructive leadership, or implement new policies, or empower followers. It’s about the interplay between leader traits, follower dynamics, and environmental factors. By identifying and addressing each component, it’s possible to prevent or change harmful leadership structures.

“You Just Need to be More Assertive”

Followers are sometimes blamed for not speaking up about a harmful situation, when it is actually the centralization of power and the nature of the hierarchical control that disempowers followers. The less powerful can find themselves in an impossible situation where lifting themselves up ends with a ceiling that collapses back onto them.

Empowering followers without addressing destructive leadership can actually increase their risk of harm, as destructive leaders are likely to see follower assertiveness as disloyal, disrespectful, and a threat to their power.

So when someone says, “You just need to speak up,” it overlooks a critical truth: In systems like this, speaking up often increases risk. You may be blamed, marginalized, or discredited not because you’re wrong, but because you disrupted the performance.

“We Just Need Better Policies”

Implementing new policies without addressing destructive leadership can give an abusive system the appearance of legitimacy and safety without the character needed to follow through with those policies with integrity. Policies alone don’t make a place safe.

“We Just Need a New Leader”

Removing destructive leadership without addressing the environment and culture can result in replacing the old with something similar as before. The next leader may carry the same destructive traits or be selected precisely because they do.

Naming the System

When the triangle is intact, the system reinforces itself. An organization or culture that perpetuates abuse will question the motives of those who ask questions, make the discussion of problems the problem, condemn those who condemn, silence those who break silence, and descend upon those who dissent.

The leader punishes dissent.

The followers protect the leader.

The environment dismisses complaints.

Around and around it goes.

In response, it’s easy to tell yourself, “I should’ve said something.” “I shouldn’t have trusted them.”“I must be the problem.” But systems are powerful. Because they are often deeply structured and reinforced, they are not easily resisted, especially alone.

One way to resist is to see the system at work and identify its toxicity. Being able to name and describe the different parts of the system and how they are all connected can be an important step to freedom and recovery. You may have been made to believe that naming what was happening would destroy everything. But naming the truth doesn’t destroy what’s good. It exposes what’s false. That can be the beginning of clarity, and clarity can pave the way to freedom and empowerment.