Truth-telling is a difficult high road that sometimes requires confronting deceptive and abusive people who have taken the easy low road of truth-repelling. One of the tactics used by deceptive people or organizations when exposed is to turn that landscape upside-down.

For example, the abusive person or organization might give others the impression that they are the ones who have taken a difficult high road of pursuing peace, inviting reconciliation, letting go of the past, demonstrating love, and promoting unity.

This rotating of the map simultaneously gives the impression that those speaking truth to power have taken the easy low road of pursuing revenge, rejecting reconciliation, spreading gossip, harboring bitterness, demonstrating hate, and promoting division.

It’s a twisting of reality seen all too often within cultures that perpetuate abuse. They question the motives of those who ask questions, make the discussion of problems the problem, condemn those who condemn, silence those who break silence, and descend upon those who dissent.

In this post, I introduce some tactics offenders and enablers use to discredit truth-tellers. I see it ultimately as an issue of power and the ways in which power is gained, retained, and challenged, so I start with a note about the nature of power.

Power to the Powerful

Judith Herman wrote, “The more powerful the perpetrator, the greater is his prerogative to name and define reality, and the more completely his arguments prevail.”1

Power accrues to the powerful. Part of the challenge with speaking out about abusive power is that it is the nature of power that it’s directed to those who already hold the microphone. A common leadership response to threats to power is to centralize that power so that decision making and information control is kept within the highest levels of authority, which only increases the power differential and the risk to vulnerable people. And with that microphone, they define the situation for others so others cannot define it for themselves. They determine the language: the rules of vocabulary and grammar that others must follow when thinking and speaking about the matter. This power to twist reality can result in victim-survivors being disempowered and robbed of voice and choice.2

A community can also amplify these discrediting messages, especially when loyalty and betrayal are common themes used to promote silence. When a powerful person puts the theme of betrayal above all else, those closest to them are put to the test. The purity of one's loyalty might only be confirmed by enabling the punishment of those who threaten the status quo. Conformity to a powerful person or entity can result in hostility to any who challenge it, and that hostility is often fueled by false narratives.

These false narratives actively work against the goals of safety as the community is led to shun or condemn truth-tellers. A pattern of controlling the narratives of victim-survivors can destroy any hope they have of finding peer support on their journey towards seeking truth and repair.

This deception that can cause loving friends and family to become torn apart, demonstrating how quickly and easily people can betray fundamental values like truth. It takes much support, moral courage, and patience to challenge what seems to be unquestionable.

Condemnation of the Condemners

A common response to exposure of wrongdoing is to assert ones innocence, even if that requires displacing guilt and shame onto those already betrayed and victimized.

This is not a new phenomenon. In the 1950s, two researchers found that individuals tend to use five different techniques to neutralize their own sense of what is right and wrong and therefore escape feelings of guilt and shame when exposed. They called one of the those techniques condemnation of the condemners in which the offender maintains that those who condemn the wrong do so out of spite or are hypocritical and are unfairly shifting the blame off themselves.3 Researchers have since sought to observe this technique in a variety of contexts.

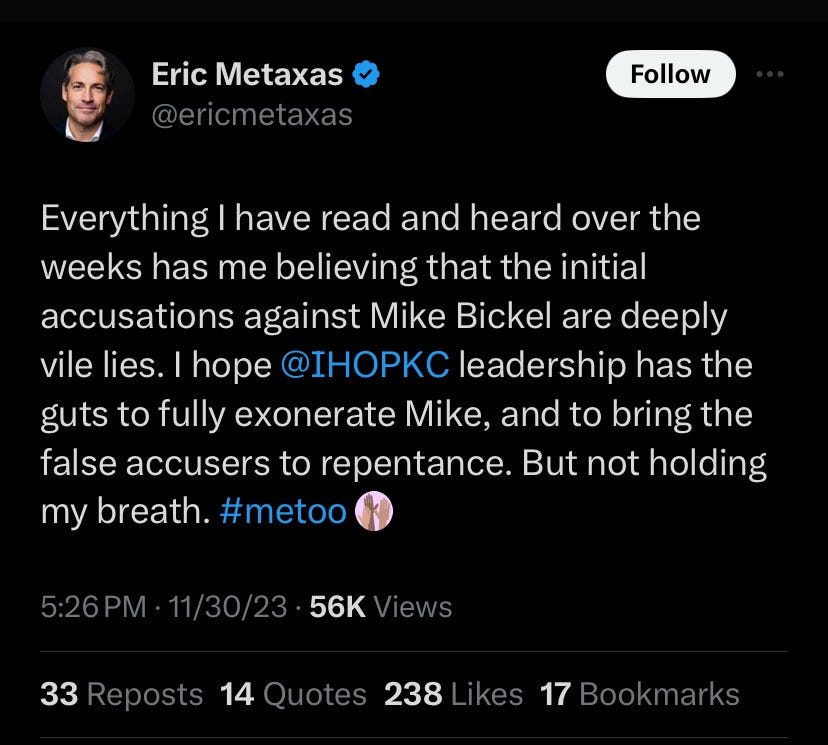

A recent example of condemning the condemners might be found in a response by author Eric Metaxas to those who reported that Mike Bickle, founder of a well-known ministry called International House of Prayer (IHOP), had abused those under his leadership. Metaxas called the reports “deeply vile lies” made by “false accusers”:

Then, about 2 weeks later, Bickle released a statement in which he admitted to engaging in “inappropriate behavior.”4 Not long after that, IHOP announced it had “received new information to now confirm a level of inappropriate behavior on the part of Mike Bickle that requires IHOPKC to immediately formally and permanently separate from him.”5

Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim-Offender (DARVO)

Similar to the concept of condemning the condemners is a response that denies responsibility and then attacks the truth-tellers, thereby giving the impression that the offender is the real victim. Jennifer Freyd introduced the term "DARVO" in a paragraph near the end of a 1997 publication about her primary research focus, "betrayal trauma theory.”6

I have recently begun to think about a way to conceptualize the events that occur when a victim or a concerned observer openly confronts an abuser about his or her behavior after a long period of silence in which the abuser could abuse without facing consequences. My proposal, currently, very speculative, is that frequent reaction of an abuser to being held accountable is the ‘DARVO’ response. ‘DARVO’ stands for ‘Deny, Attack and Reverse Victim and Offender’. It is important to distinguish types of denial, for an innocent person will probably deny a false accusation. Thus denial is not evidence of guilt. However, I propose that a certain kind of indignant self-righteous, and overly stated, denial may in fact relate to guilt. I hypothesize that if an accusation is true, and the accused person is abusive, the denial is more indignant, self-righteous and manipulative, as compared with denial in other cases. Similarly, I have observed that actual abusers threaten, bully and make a nightmare for anyone who holds them accountable or asks them to change their abusive behavior. This attack, intended to chill and terrify, typically includes threats of law suits, overt and covert attacks on the whistle-blower’s credibility, and so on. The attack will often take the form of focusing on ridiculing the person who attempts to hold the offender accountable. The attack will also likely focus on ad hominem or ad feminam instead of intellectual/evidential issues. Finally, I propose that the offender rapidly creates the impression that the abuser is the wronged one, while the victim or concerned observer is the offender. Figure and ground are completely reversed. The more the offender is held accountable, the more wronged the offender claims to be. The offender accuses those who hold him accountable of perpetuating acts of defamation, false accusations, smearing, etc. The offender is on the offense and the person attempting to hold the offender accountable is put on the defense. ‘Deny, Attack and Reverse Victim and Offender’ work best together. How can someone be on the attack so viciously and be in the victim role? Future research may investigate the hypothesis that the offender rapidly goes back and forth between ‘attack’ and ‘reverse victim and offender’.

There are many ways in which offenders and enablers might attack the credibility of truth-tellers or seek to silence them. Beyond intimidation and threats, more subtle messages might seek to cast truth-tellers and their supporters in the worst possible light by:

Amplifying and exaggerating any perceived negative characteristics or stereotypes (“Why didn’t they speak up sooner?”),

Belittling any positive characteristics like integrity (“They’re not really interested in right and wrong if they’re speaking out to others.")

Unfairly associating them with people or ideas they deem untrustworthy (“They’ve been reading/following _____”)

Unfairly separating them from people or ideas they deem trustworthy (“They walked away from the faith.”)

All of these varied attacks on the credibility of the truth-tellers, combined with an array of denials and victim-stancing tactics, generates a dizzying twisting of narrative that can confuse and disorient. Truth-tellers can, with the support of others, try to keep their footing while the ground spins so they do not lose sight of the distinguishing factor: truth. Those on the high road will consistently invite the discovery of truth while those on the low road will consistently repel and confuse it.

Anti-DARVO

Jennifer Freyd and her colleagues propose that the antidote to DARVO within organizations is institutional courage. They give ten general principles that can be applied across a variety of contexts. I end this post by including the first four below, but you can find all ten here.7

1. Comply with criminal laws and civil rights codes.

Go beyond mere compliance. Avoid a check-box approach by stretching beyond minimal standards of compliance and reach for excellence in non-violence and equity.

2. Respond sensitively to victim disclosures.

Avoid cruel responses that blame and attack the victim. Even well-meaning responses can be harmful by, for instance, taking control away from the victim or by minimizing the harm. Better listening skills can also help institutions respond sensitively.

3. Bear witness, be accountable and apologize.

Create ways for individuals to discuss what happened to them. This includes being accountable for mistakes and apologizing when appropriate.

4. Cherish the whistleblower.

Those who raise uncomfortable truths are potentially the best friends of an institution. Once people in power have been notified about a problem, they can take steps to correct it. Encourage whistleblowing through incentives like awards and salary boosts.

Herman, J. (2015). Trauma and recovery. Basic Books.

For more on the significance of empowerment, voice, and choice, see https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

Sykes, Gresham M and David Matza. 1957. “Techniques of Neutralization: A Theory of Delinquency.” American Sociological Review 22(6):664. doi:10.2307/2089195

https://www.washingtonpost.com/religion/2023/12/14/mike-bickle-ihop-confess-misconduct/

https://www.kansascity.com/news/local/article283459528.html

https://dynamic.uoregon.edu/jjf/articles/freyd97r.pdf

https://theconversation.com/when-sexual-assault-victims-speak-out-their-institutions-often-betray-them-87050