The abusive person is a shape shifter who is constantly adjusting appearances depending on the situation, goal, and audience. Coercive tactics are not fixed but fluid, used interchangeably and strategically. What works on one person in one moment might not work on another, and so the abuser adapts, often at dizzying speed.

For example, it’s not unusual for an abuser to play both lion and lamb. The lion intimidates and frightens, cultivating fear. The lamb pleads innocence, cultivating sympathy. Both personas serve the same purpose: control.

This concept of shifting identities echoes the Face Dancers from Frank Herbert’s Dune series—creatures capable of transforming their physical form and voice to mimic others. They don’t merely hide; they become. They twist the truth by reshaping perception itself.

Reinforcing the Coercive Cycle

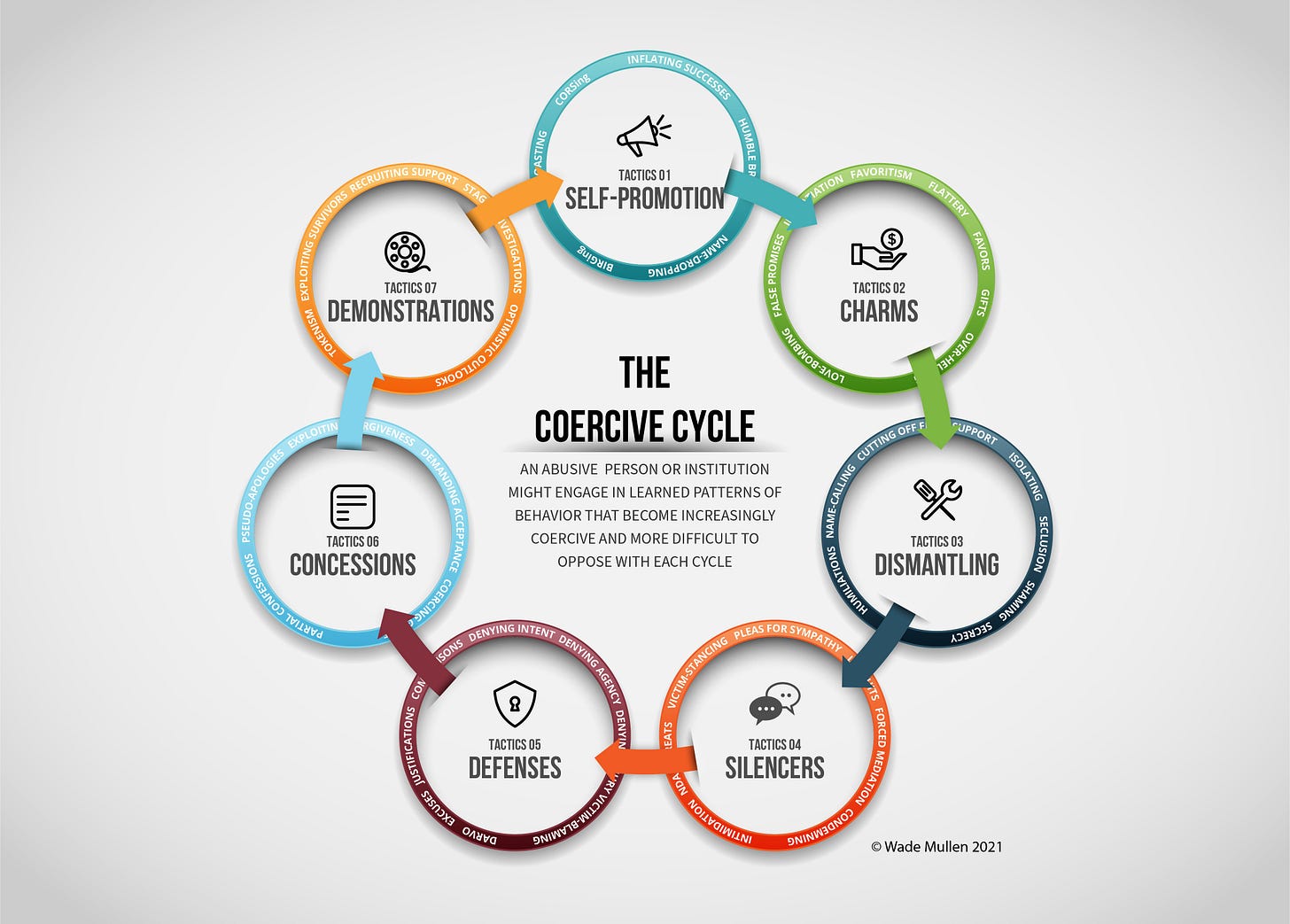

As the abuser experiments and adapts, patterns are reinforced. What worked before is likely to be repeated. Dozens of tactics, such as charm, silence, shame, flattery, or fear, can be used interchangeably to maintain control. I’ve visualized this dynamic in a coercive cycle diagram, which I introduced a few years ago.

Early charm, for example, might be used to manufacture trust, making later violations easier. The abuser may begin by taking small liberties cloaked in coded language or ambiguous gestures, testing boundaries while maintaining plausible deniability.

If questioned, they’ll claim misunderstanding. “I didn’t mean it that way,” or “You’re overreacting.” This leaves the target in a precarious position: speak up and risk retaliation, or stay silent and risk further erosion of boundaries.

As control deepens, other tactics emerge like humiliation, isolation, guilt. And just when needed, charm might return, now recycled to confuse and disarm.

Interchanging Faces: The Art of Disorientation

The constant shape shifting is a core reason abusive relationships can feel so confusing. The gaslighting begins not only in what’s said but in who appears before you. Is this the same person? Was the lion just a bad moment? Is the lamb who they truly are?

This mirrors sociologist Erving Goffman’s theory of impression management: we are all actors on a stage, adjusting our scripts based on audience response. For the abusive individual, this performance is finely tuned. They learn what impression to present to which person, when, and how.

Research has shown these strategies can become interchangeable and automatic.1 The goal? To be seen in the most favorable light possible. To control the narrative. To ensure only the version of themselves that appears safe, good, and respectable is seen by others. Meanwhile, their abuse continues behind the curtain.

It’s why different people can have vastly different impressions of the same person at the same time.

Even nature echoes this duality. Marine biologist David Gallo describes how male squid can split their color displays when showing a soft brown side to attract a mate while displaying a stark white warning to rival males. One creature, two faces, simultaneously.

Setting the Stage for Disbelief

This performance also sets the stage for disbelief.

Because the abuse is often hidden or directed at those with less power, victims who speak up are met with confusion and suspicion. “That doesn’t sound like the person I know.” Of course it doesn’t because the abuser tends to control what is known.

Nathan Pyle illustrates this well in a comic where two eagles wonder why Mr. Mouse calls the owl a predator. “He’s never bothered us,” they say.

They simply weren’t prey.

Do they know what they are doing?

A common question I receive is whether abusive people are aware they are engaging in patterns of manipulation.

Awareness is complex and varies. Some researchers argue these behaviors can be intuitive or semi-conscious and are learned over time through repeated trial and error, rather than consciously plotted.

Still, even if the tactics become second nature, there’s often an underlying awareness that they are shaping perceptions, managing impressions, and hiding parts of themselves.2

This resonates with Joseph Brodsky’s statement on the connection between consciousness and deception:

The real history of consciousness starts with one’s first lie.

Others have compared these behaviors to the use of “scripts” that are developed over time and used automatically, like speaking a second language fluently. The performer knows they are performing, even if they don’t stop to reflect on every line. A person may process a series of events automatically, using scripts previously relied upon in similar situations. If the script proves ineffectual, then the individual is likely to revert to an alternative script based on his semi-conscious understanding of the target’s perceptions. Thus, a person may develop a flexible script over time that can be altered on the basis of how the target is receiving the script.3

Yet even if one becomes so habituated in their deception that they can shift without stopping to think about their next move, they may at least maintain the knowledge that they are not being truthful.

Again, Brodsky offers a haunting echo:

…devising all kinds of detours, arranging shady deals with one’s superiors, piling up lies and pulling the strings of one’s semi-nepotic connections. This would become a full-time job. Yet one was constantly aware that the web one had woven was a web of lies, and in spite of the degree of success or your sense of humor, you’d despise yourself.

Getting on the Balcony

So what are you to do when facing this whirlwind of lies, personas, and shifting tactics?

Leadership literature offers a concept called getting on the balcony. It means stepping back from the dance floor to get a clearer view of the patterns, the movements, the forces at play.

For some this might not be possible or safe, but if it is, it can afford you the opportunity to take an inventory of what you know to be true without the gaslighting effects. It allows you to go at your speed, not theirs. It can give you a wider perspective of the patterns you see stretched out across time, events, situations, and people.

In the context of abuse, this might mean creating space—physically, emotionally, mentally—so you can reflect without being pulled back into the cycle. It might mean writing a timeline, connecting dots, seeing what was hidden when you were too close to see clearly.

It might mean seeking a trusted support person to help you name what you’re experiencing and make sense of the many shapes and faces.

If this resonates, you are not alone. Many have encountered shape shifters and face dancers in their lives. But in seeing the pattern, you begin to reclaim power. Naming it is one step toward breaking the spell.

Looking Ahead

Next week, I’ll explore The Toxic Triangle, a framework developed by leadership researchers to explain how destructive leaders gain and maintain power. It highlights the interplay between three forces: the leader’s destructive behavior, the vulnerability of followers, and an environment that allows abuse to thrive. This model helps us see abuse not just as an individual problem, but as a systemic one. Understanding the triangle can help us recognize warning signs, break harmful patterns, and build healthier communities.

Caillouet, Rachel Harris, "A Quest for Legitimacy: Impression Management Strategies Used by an Organization in Crisis." (1991). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5110. Marcus, A. A., & Goodman, R. S. (1991). Victims and Shareholders: The Dilemmas of Presenting Corporate Policy during a Crisis. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 281-305.

Tseëlon, E. (1992). Is the Presented Self Sincere? Goffman, Impression Management and the Postmodern Self. Theory, Culture & Society, 9(2), 115-128.

Bozeman, D. P., & Kacmar, K. M. (1997). A cybernetic model of impression management processes in organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 69(1), 9–30.